Encoding PubMed abstracts for NLP tasks

Published on | 5 min read

Last month, I gave a talk at a local meetup on LLMs, LangChain & SQL. Since then, I’ve wanted to explore the technical foundations of LLMs, particularly neural networks.

This article will begin a series of technical tutorials that are geared towards healthcare care use cases. While there is no shortage of resources to learn about LLMs, neural networks, or the latest ML algorithms, my focus will be to reinforce technical concepts related to deep learning.

A simple approach to NLP: One-hot encoding

To start, I wanted to backtrack the origins of LLMs, which are a type of neural network. A neural network is a type of machine learning approach that attempts to mimic the way the brain works (biological neural network). This approach has been shown to perform better on NLP tasks than previous methods. For a great overview of NLP, check out this guide.

The goal of NLP is to enable computers to “understand” natural language in order to perform some task, such as sentiment analysis. In order to do so, natural language (text) has to be converted (encode) into a numerical format.

There are numerous approaches to encode text, with more advanced approaches surfacing over the years. I will start with one-hot encoding, as it is one of the most familiar data pre-processing techniques for ML. However, we will also begin to see the limitations of such a technique through the example below.

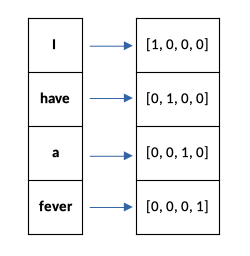

For NLP, one of the simplest techniques for encoding text is to represent each categorical variable (a word) as a binary vector. A one-hot vector can be thought of as a type of binary vector where the index of the word is denoted as ‘1’, and all other words are denoted as ‘0’. The size/dimension of the vector is determined by the total number of unique words (vocabulary) found in the text.

Consider the following text: ‘I have a fever’. The vocabulary consists of 4 unique words (I, have, a, fever), and each word is represented as a one-hot vector.

Let’s convert a few PubMed abstracts to one-hot vectors

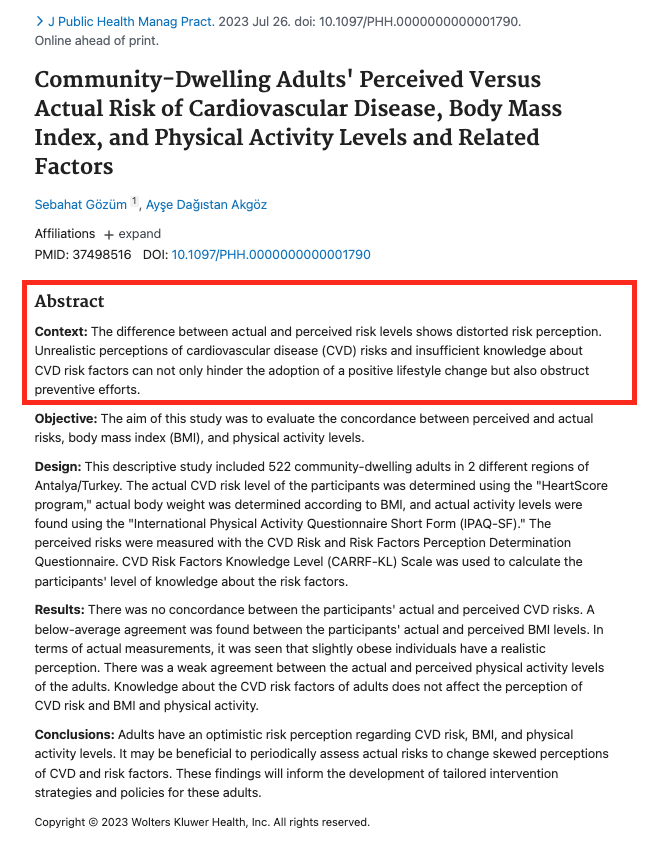

To put the above tutorial into practice, I thought I would give this a try with a few abstracts. Let’s say that we want to perform an NLP task on papers that discuss cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors. This is what my query and results look like in PubMed:

Each abstract represents a single document in a corpus (collection of documents). Let’s take the first 5 words from each abstract. For simplicity purposes, we will ignore header terms such as ‘Context’, ‘Introduction’, ‘Purpose’.

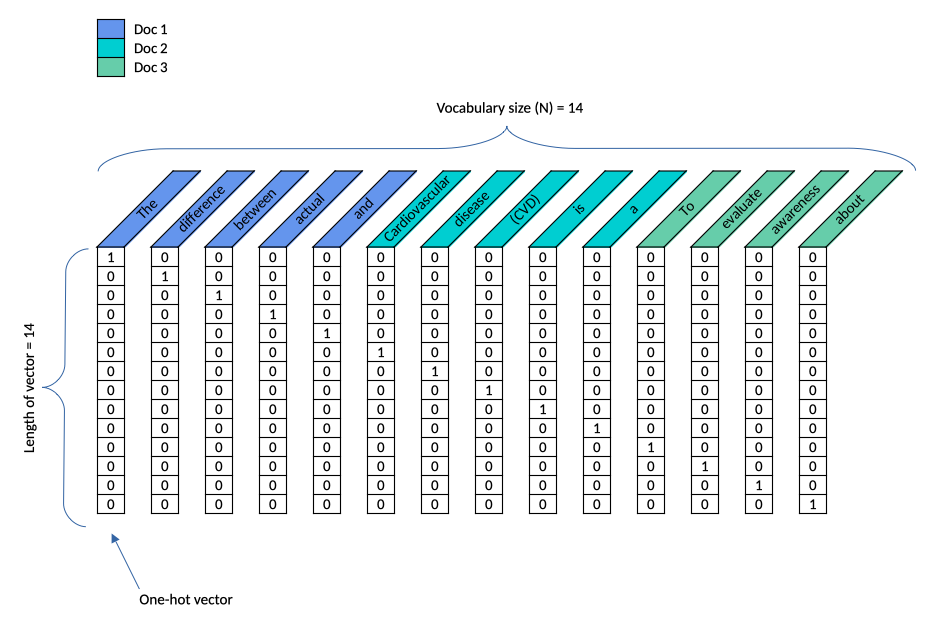

There are 15 words in the corpus:

Doc 1: “The difference between actual and”

Doc 2: “Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a”

Doc 3: “To evaluate awareness about cardiovascular”

Next, we need to find the unique words. We have 14 unique words (‘cardiovascular’ is repeated twice):

Doc 1: The(1) difference(2) between(3) actual(4) and(5)

Doc 2: Cardiovascular(6) disease(7) (CVD)(8) is(9) a(10)

Doc 3: To(11) evaluate(12) awareness(13) about(14) cardiovascular(6)

We represent these unique words in a vocabulary:

Vocabulary = {‘The’, ‘difference’, ‘between’, ‘actual’, ‘and’, ‘Cardiovascular’, ‘disease’, ‘(CVD)’, ‘is’, ‘a’, ‘To’, ‘evaluate’, ‘awareness’, ‘about’}

Each word is represented as a one-hot vector with a length equal to the size of the vocabulary (N = 14). We will have something that looks like this:

Limitations of one-hot encoding

One challenge seen with the one-hot encoding approach is that there is no information about the words the vectors represent, or how the words relate to each other. That is, it tells us nothing about the similarities or differences between words. If we were to graph each vector and calculate a similarity measure (e.g., cosine similarity) between them, we would see that there is 0 similiarity between any two vectors. Refer to this article for a mathematical overview of the concept.

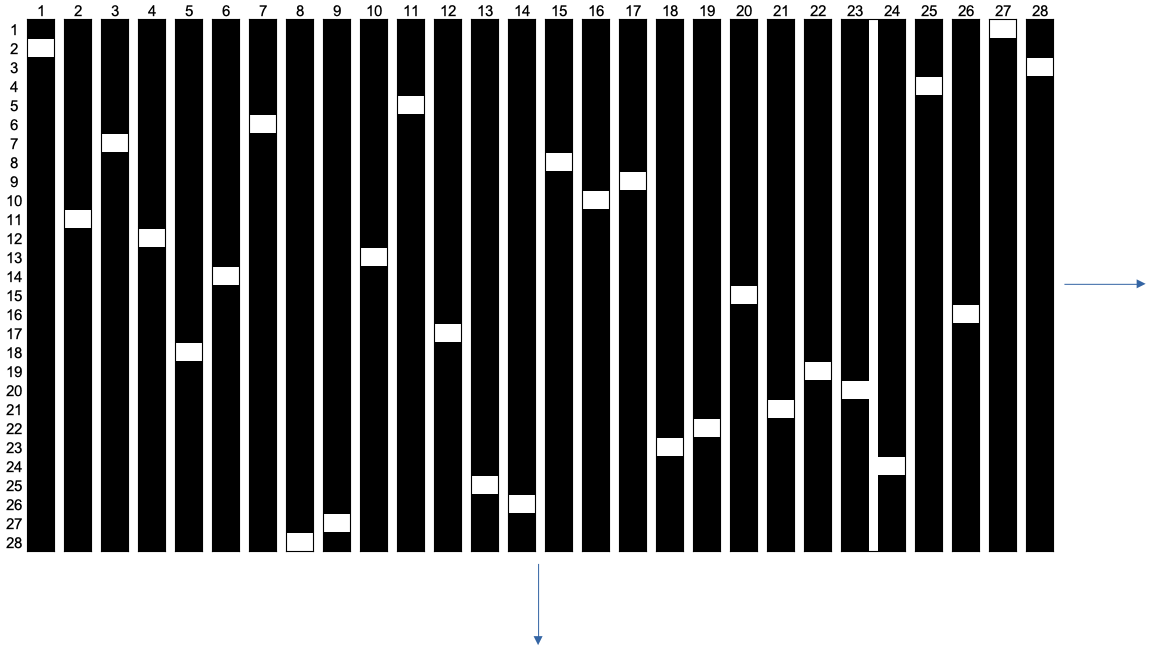

A second challenge is sparse, highly dimensional data. When each word in a document is replaced with a one-hot vector, we start to get a large feature space with a lot of zeroes. In fact, when increase our vocabulary size (for example, double the vocabulary size N = 28 words), the feature space will morph into something like this:

This dataset is:

- sparse (majority of the elements are zeroes)

- highly-dimensional (a larger vocabulary creates a larger feature space, which requires more computational power and data)

- hard-coded (machine does not learning anything from the data)

Given these limitations, this technique makes it difficult for a computer to detect any sort of meaningful patterns to make an accurate prediction.

Conclusion

In this tutorial, we explored one-hot encoding, a very simple way to convert categorical variables for natural language processing tasks. By taking a subset of PubMed abstracts, we were able to see how this approach becomes highly inefficient with larger vocabularies. Some of these inefficiencies are due to a lack of understanding relationships between words, as well as a sparse and highly-dimensional feature space.

There have been different techniques that have improved upon the limitations of one-hot encoding, and they have worked increasingly well with neural networks. I will explore these in future posts.

References

- https://www.deeplearning.ai/resources/natural-language-processing

- https://web.stanford.edu/class/cs224n/readings/cs224n-2019-notes01-wordvecs1.pdf

- https://developers.google.com/machine-learning/glossary#one-hot-encoding

- https://www.tensorflow.org/text/guide/word_embeddings

- https://medium.com/intelligentmachines/word-embedding-and-one-hot-encoding-ad17b4bbe111

- https://builtin.com/data-science/curse-dimensionality

- https://towardsdatascience.com/word-embeddings-intuition-behind-the-vector-representation-of-the-words-7e4eb2410bba

- https://wordcount.com/